Gustav Klimt occupies a singular place in art history, his fame bordering on that of a celebrity, and his work transcending its historical moment to become a global cultural symbol. In the art world, his paintings are instantly recognisable, not only for their gilded surfaces and sensual intensity, but for the aura of myth, glamour, and psychological depth that surrounds them. Yet Klimt’s status as an artistic legend did not emerge from style alone. It is the product of a complex interplay between lots of factors which influenced him as an artist, i.a. his experiences, his character, or cultural context.

Klimt’s rise was forged in the charged atmosphere of fin‑de‑siècle Vienna, a city where intellectual ambition, social tension, and artistic rebellion collided. His personal story, marked by early academic success, personal tragedy, and a decisive break from institutional authority, became inseparable from the evolution of his art. His “golden period” crystallised a visual language that fused ornament, myth, and sensuality into something both ancient and radically modern. And over time, the narratives surrounding Klimt, presenting him as the rebel, the visionary, the chronicler of a gilded world on the brink of collapse, have amplified his cultural weight far beyond the confines of art history.

Table of Contents

- Key Forces That Shaped Klimt’s Artistic Mastery

- Foundations of Rebellion

- The Intellectual Ferment of Fin‑de‑Siècle Vienna

- Exposure to Global Aesthetics and Decorative Traditions

- The “Golden Period” as a Unique Artistic Signature

- A Deep Engagement with Archetype and Myth

- How Klimt’s Imagery Creates Universal Appeal Across Cultures and Markets

- Klimt as a Symbol of Fin‑de‑Siècle Glamour and Rebellion

This article examines the constellation of forces that shaped Klimt’s identity, in particular the biographical currents that influenced his vision, the stylistic breakthroughs that defined his signature painting style and the very outstanding imagery that has been resonating across decades. Klimt has become not only a symbol of Vienna’s most dazzling and turbulent era, but also one of the most sought-after painters of the XXI century. Gustav Klimt continues to captivate, seduce, and shape the cultural imagination more than a century after his death in 1918. He has endured not merely as a painter but as a phenomenon whose works command eye‑watering prices at major auctions around the world.

Back to topKey Forces That Shaped Klimt’s Artistic Mastery

Gustav Klimt occupies a singular place in modern art, but it is worth remembering that his brilliance did not emerge in isolation. His artistic mastery was forged through a dynamic blend of personal experience, cultural upheaval, and bold aesthetic experimentation. Understanding the forces that shaped his vision reveals not only how he became a defining figure of modern art but also why his work continues to resonate so powerfully today.

His paintings are instantly recognisable, not only for their gilded surfaces and sensual intensity, but for the aura of myth, glamour, and psychological depth that surrounds them. Yet Klimt’s legendary status did not arise from style alone. It emerged from a complex interplay of biography, cultural context, aesthetic innovation, and narrative power. To understand why he resonates so profoundly today across continents, markets, and generations, one must look beyond the surface and into the forces that shaped both the man and his legacy.

A Formative Academic Foundation

A formative academic foundation shaped Klimt long before he became the emblem of Viennese modernism. In 1876, at the age of 14, he was admitted to the Kunstgewerbeschule (Vienna School of Arts and Crafts, now the University of Applied Arts Vienna), where he absorbed a rigorous, craft‑driven education that emphasised precision, anatomy, architectural proportion, and the disciplined execution of large‑scale decorative programs.

Actually, according to the Leopold Museum, it seems that Klimt was seemingly predestined to define the aesthetic of the Vienna Ringstrasse, as his rigorous academic training made him the ideal candidate to decorate the "palaces" of a wealthy bourgeoisie eager to cement their social status. In 1883, he formed the studio collective “Künstlercompagnie” (the "Company of Artists") alongside his brother Ernst and Franz Matsch, capitalizing on the city's feverish building boom. Through this partnership, Klimt’s talent became central to the most prestigious projects of the era; his hand guided the execution of the grand ceiling paintings for the Burgtheater staircases (1886–1888) and the meticulous spandrel and intercolumnar works for the Kunsthistorisches Museum (1887–1891).

A Decisive Break from Institutional Authority

A decisive break from institutional authority marked the turning point in Klimt’s evolution from a gifted academic painter into a radical modernist. By the mid‑1890s, he had become one of Vienna’s most successful decorative artists, celebrated for his technical precision and monumental commissions.

However, after the deaths of his father and brother, Gustav Klimt’s artistic output came to a halt. By that point, he had already begun questioning the conventions of academic painting, a shift that led to growing tensions with Franz Matsch. In 1893, a Ministry of Education advisory committee approached Matsch to help design the ceiling for the newly built Great Hall at the University of Vienna. Whether the invitation came from Matsch or the Ministry, Klimt eventually joined the project, which turned out to become the last collaboration.

Klimt’s monumental ceiling paintings: Philosophy (1897–98), Medicine (1900–01), and Jurisprudence (1899–1907) were condemned for their radical themes and materials, with some critics even calling them ‘pornographic.’ In these works, Klimt recast traditional allegory and symbolism into a new visual language that was more openly erotic and, for many, deeply unsettling. The nudity of several figures in Gustav Klimt’s university paintings, along with accusations of ambiguity, sparked intense public debate. In the aftermath, Klimt vowed never again to accept a public commission. The backlash came from every direction, including political, aesthetic, and religious circles, and ultimately, the paintings were never installed on the ceiling of the Great Hall.

The Vienna Secession

In 1897, he led a group of like‑minded artists in founding the Vienna Secession, a bold declaration of independence from academic authority and a commitment to artistic freedom. Interestingly, the group issued no manifesto and avoided promoting any single style; Naturalists, Realists, and Symbolists all worked side by side. The government backed their initiative, granting them a lease on public land to build an exhibition hall. The Vienna Secession adopted Gustav Klimt’s 1898 painting of Pallas Athena as its symbol. The striking image of the Greek goddess associated with justice, wisdom, and the arts is now housed in the Vienna Museum.

Back to topFoundations of Rebellion

Without Klimt, there would be no Viennese Secession, which was created out of his sheer rebellion. However, Klimt’s defiance did not appear out of nowhere. His early years unfolded against the backdrop of Vienna’s Ringstrasse era, a period defined by grandeur and strict academic conventions, which did not tolerate a more modern perspective, Klimt's perspective. All those forces influenced his visions and ambitions, and ultimately pushed him toward the rebellious path that would redefine modern art.

The Ringstrasse Era gave him "The Keys to the City"

Because Klimt proved himself with the Burgtheater and the Kunsthistorisches Museum, he earned the trust of the state. This wasn't just about money; it gave him the social capital and financial independence to later rebel. When he eventually broke away to form the Secession, he wasn't a "starving artist" shouting from the sidelines. He was a decorated master walking away from the peak of the establishment, which made his rebellion far more scandalous and impactful.

Mastery Before Subversion

His early success with the Künstlercompagnie proved he could paint better than almost anyone in the traditional style. This is crucial for his further success because it meant that when he eventually moved toward symbolism and "The Golden Phase," critics couldn't claim he was "hiding" a lack of talent behind abstract patterns. His radicalism was seen as a deliberate choice, not a technical limitation.

The Catalyst of Tragedy

The charged atmosphere of his early success was held together by the collective. However, the death of his brother Ernst in 1892 (shortly after the Kunsthistorisches Museum project) shattered the Künstlercompagnie. This personal crisis, combined with his boredom with academic constraints, acted as a catalyst. Without that early period of "fitting in," he might never have felt the intense need to break out. It is possible to notice the shift in his work at the Kunsthistorisches Museum. While the figures are academic, the way he framed them and the intensity of the female gazes began to hint at the "Klimt Woman" who would later define his greatest masterpieces.

Direct Access to the Elite

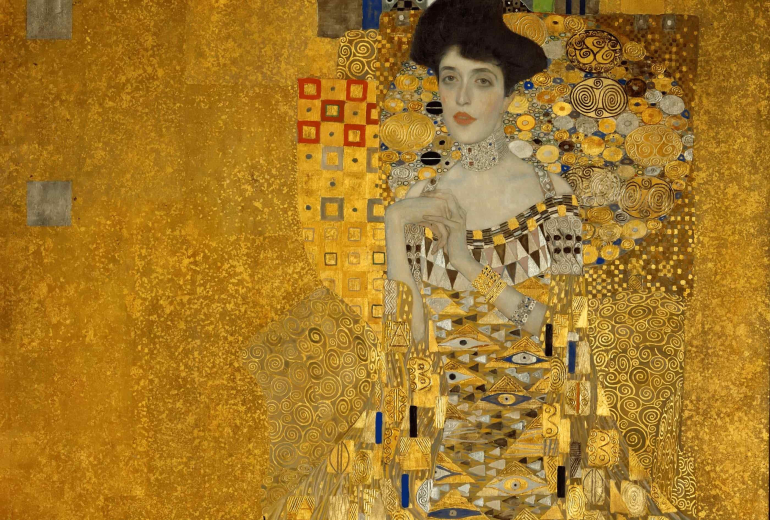

The bourgeois families who hired him for their Ringstrasse palaces became his lifelong patrons. Even after he turned his back on the state and the Academy, these wealthy families (like the Bloch-Bauers) continued to commission the private portraits that we now recognize as his most famous works, such as the Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer.

Back to topThe Intellectual Ferment of Fin‑de‑Siècle Vienna

The intellectual ferment of fin‑de‑siècle Vienna provided the cultural oxygen that allowed Klimt’s artistic transformation to ignite. At the turn of the century, the city was a crucible of radical thought, where traditional certainties were dissolving under the pressure of new ideas in psychology, philosophy, music, literature, and the sciences. Freud was uncovering the architecture of the unconscious; Schnitzler was dissecting desire and repression; Mahler was reshaping musical form; Wittgenstein was redefining the limits of language and logic. This atmosphere of questioning — of probing beneath the surface of appearances — resonated deeply with Klimt. He absorbed the era’s fascination with the psyche, symbolism, and the hidden forces that shape human experience, translating these currents into a visual language that was both ornamental and psychologically charged. The Secession itself embodied this intellectual spirit: a movement that rejected academic dogma in favour of experimentation, cross‑disciplinary exchange, and the belief that art should reflect the complexities of modern life. Klimt’s work became a mirror of this cultural moment, capturing its anxieties, its sensuality, its yearning for transcendence, and its confrontation with the unknown. In this environment, Klimt did not merely paint; he participated in a broader reimagining of what it meant to be modern.

Back to topExposure to Global Aesthetics and Decorative Traditions

Exposure to global aesthetics and decorative traditions expanded Klimt’s visual imagination far beyond the boundaries of Viennese academic painting. His encounter with Byzantine mosaics in Ravenna was transformative: the shimmering gold, flattened space, and hieratic frontal figures offered a model for an art that could be both sacred and sensuous. Japanese woodblock prints introduced him to asymmetry, contour, and the expressive power of pattern, while Egyptian, Mycenaean, and Near Eastern motifs enriched his ornamental vocabulary with symbols that felt timeless and universal. Klimt absorbed these influences not as quotations but as raw material for synthesis. He blended the spiritual luminosity of Byzantine art with the graphic clarity of Japonisme and the rhythmic geometry of ancient ornament, creating a hybrid aesthetic that felt at once archaic and radically modern. This cosmopolitan openness allowed him to escape the confines of European naturalism and develop a visual language rooted in pattern, abstraction, and symbolic resonance. It is this fusion — global, historical, and deeply personal — that gives Klimt’s work its unmistakable identity and enduring cross‑cultural appeal.

Back to topThe “Golden Period” as a Unique Artistic Signature

Klimt’s so‑called “golden period” — spanning the first decade of the twentieth century — represents one of the most instantly recognisable and commercially powerful stylistic signatures in modern art. During these years, Klimt fused influences from Byzantine mosaics, medieval icon panels, and Japanese decorative traditions into a visual language that was both archaic and radically modern. His use of gold leaf, applied with extraordinary technical precision, created surfaces that oscillate between painting and object, image and icon. This material opulence is not merely decorative; it functions as a symbolic device, elevating his sitters into timeless, almost sacred figures and transforming portraiture into a form of secular reliquary.

What distinguishes the golden period in today’s market is its combination of rarity, recognisability, and narrative power. Works from this phase are few, tightly held, and disproportionately represented among Klimt’s most celebrated paintings — from Judith I to Portrait of Adele Bloch‑Bauer I. Their scarcity is compounded by the fact that Klimt produced them slowly and with meticulous craftsmanship, often reworking surfaces for months. As a result, golden‑period paintings have become a category unto themselves: a micro‑brand within Klimt’s oeuvre that commands a premium because it encapsulates the apex of his innovation.

The golden period also aligns uncannily with contemporary tastes. In an era defined by luxury culture, global wealth, and the visual language of opulence, Klimt’s gilded surfaces resonate across markets from Europe to Asia and the Gulf. The interplay of flat ornament and psychological intensity — a hallmark of these works — offers both aesthetic richness and emotional depth, appealing to collectors who seek art that is visually spectacular yet symbolically layered. This duality explains why golden‑period paintings consistently achieve the highest valuations and why they serve as the anchor of Klimt’s market identity.

Ultimately, the golden period functions as Klimt’s artistic signature in the strongest sense: a style that is unmistakable, materially seductive, historically significant, and deeply aligned with the desires of the twenty‑first‑century collector. It is the phase that transformed Klimt from a leading Viennese painter into a global cultural icon — and it remains the engine of his enduring market power.

Back to topA Deep Engagement with Archetype and Myth

A deep engagement with archetype and myth runs through Klimt’s work, giving it a resonance that transcends its historical moment. Rather than depicting specific narratives or literal stories, he drew on symbolic forms that tap into universal human experience — the femme fatale, the mother and child, the lovers entwined, the cycle of life and death, the tree of life as a bridge between worlds. These motifs allowed him to communicate emotional and psychological truths without relying on traditional religious or academic iconography. Klimt understood that myth is not merely a set of ancient tales but a language of the subconscious, a way of expressing desire, fear, transformation, and transcendence in visual form. His figures often appear suspended between the earthly and the eternal, their bodies enveloped in patterns that evoke ritual, dream, and the timeless rhythms of nature. By weaving archetypal symbolism into a modern aesthetic, Klimt created images that feel both intimate and monumental, personal and universal. This mythic dimension is a key reason his work continues to speak across cultures and eras: viewers recognise in his paintings not just beauty, but something elemental — a visual expression of the shared human stories that lie beneath the surface of history.

Back to topHow Klimt’s Imagery Creates Universal Appeal Across Cultures and Markets

Klimt’s imagery possesses a rare universality because it operates simultaneously on aesthetic, emotional, and symbolic levels, allowing his work to resonate across cultures, geographies, and collecting traditions. His use of ornament — drawn from Byzantine mosaics, Japanese prints, Islamic patterning, and the decorative arts of the Austro‑Hungarian Empire — creates a visual language that feels both global and timeless. The intricate surfaces, geometric motifs, and shimmering gold fields appeal to collectors from regions where ornament has long been associated with refinement and prestige, including East Asia, the Middle East, and Central Europe. This cross‑cultural vocabulary gives Klimt’s paintings an immediate recognisability that transcends Western art‑historical frameworks.

Sensuality is another key component of Klimt’s universal appeal. His depictions of the female body are neither academic nor voyeuristic; instead, they occupy a psychological space that blends desire, vulnerability, and self‑possession. This emotional ambiguity allows viewers from different cultural backgrounds to project their own narratives onto the work. Klimt’s women are not passive subjects but charged presences, rendered with a modernity that continues to feel contemporary. In global markets where collectors seek art that conveys both beauty and emotional intensity, Klimt’s sensuality functions as a powerful attractor.

Myth and symbolism further expand the reach of his imagery. Klimt’s references to classical mythology, allegory, and archetypal figures tap into shared human stories that transcend national boundaries. Whether depicting Judith, Danaë, or the allegories of life and death, Klimt uses myth not as historical illustration but as a psychological framework. This approach allows his works to speak to universal themes — desire, mortality, transformation — that resonate across cultures and belief systems. In a global art market increasingly driven by narrative depth and symbolic richness, Klimt’s mythic dimension enhances both the interpretive and the commercial value of his paintings.

Together, ornament, sensuality, and myth create a visual and emotional ecosystem that is uniquely adaptable to diverse cultural contexts. Klimt’s imagery offers opulence without excess, eroticism without vulgarity, and symbolism without dogma — a combination that makes his work exceptionally portable across markets. This universality is a major reason why Klimt commands such strong demand from collectors in Europe, North America, Asia, and the Gulf, and why his paintings continue to achieve record‑breaking prices in an increasingly globalised art economy.

Back to topKlimt as a Symbol of Fin‑de‑Siècle Glamour and Rebellion

Klimt’s enduring appeal is inseparable from the narrative that surrounds him. His story was shaped by the cultural tensions, aesthetic decadence, and intellectual upheavals of fin‑de‑siècle Vienna. He occupies a unique position at the intersection of glamour and dissent, embodying both the splendour of the Austro‑Hungarian elite and the radical spirit that challenged its conventions. This duality has become central to his contemporary image: Klimt is not merely a painter of a bygone era but a symbol of its contradictions, its aspirations, and its anxieties.

On one side of this narrative lies the world of Viennese high society. Klimt’s portraits of women such as Adele Bloch‑Bauer, Eugenia Primavesi, and Elisabeth Lederer capture the opulence, fashion, and cultivated sophistication of the empire’s cultural aristocracy. These works function as visual documents of a cosmopolitan milieu defined by salons, intellectual exchange, and the aesthetics of luxury. Collectors today are drawn to this aura of refinement, a world that feels both glamorous and irretrievably lost, lending Klimt’s paintings the allure of cultural nostalgia.

Yet Klimt was equally a figure of rebellion. His leadership in the Vienna Secession positioned him at the forefront of a movement that rejected academic authority and sought artistic freedom at a moment when the empire itself was grappling with modernity. The controversies surrounding his erotic works, particularly the Faculty Paintings, cemented his reputation as an artist willing to confront social taboos and challenge the moral conservatism of his time. This defiant stance has become a defining part of his mythology, appealing to contemporary audiences who value artists that disrupt norms and expand the boundaries of expression.

The power of Klimt’s narrative lies in this tension: he is simultaneously the chronicler of a gilded world and the agent of its transformation. His work captures the splendour of an empire at its cultural peak while also signalling the psychological and aesthetic shifts that would define the twentieth century. For today’s global collectors, this narrative dimension adds a layer of symbolic capital that extends beyond formal qualities or market scarcity. Klimt represents glamour, modernity, sensuality, and resistance which together amplify the desirability of his paintings and reinforce his status as one of the most compelling figures in modern art.

Conclusion

Gustav Klimt’s artistic mastery did not emerge from a single influence or moment of revelation, but from the convergence of forces that shaped him into one of the most distinctive voices of modern art. His rigorous academic training provided the structural discipline that underpinned even his most radical experiments. Personal loss deepened his emotional register, sharpening his sensitivity to the complexities of desire, vulnerability, and mortality. The intellectual turbulence of fin‑de‑siècle Vienna exposed him to new ways of thinking about the psyche, symbolism, and the hidden architecture of human experience. Encounters with global decorative traditions expanded his visual vocabulary, allowing him to merge ancient motifs with modern abstraction. His golden period crystallised these influences into a singular aesthetic that became inseparable from his identity.

Together, these forces forged an artist whose oeuvre operates simultaneously on many levels: sensual, symbolic, and intellectual. Klimt’s paintings are not merely beautiful; they are cultural touchstones that capture the spirit of an era while speaking to enduring human truths. This is why his legacy endures with such power: Klimt did not simply reflect his world, but shaped and transformed modern art.

Back to top

Comments